Versioning with Branching Strategy

The Go team has done an amazing work with the Go modules. They gave simple, elegant and innovative solutions to any of the many hard problems in the world of code versioning and dependency management, that made our Gopher lives better and faster. Recently, the Go team has published a blog post about best practices in incrementing major versions using Go modules called “Go Modules: v2 and Beyond” 1, in which it is instructed to use a solution of copying the code into a subdirectory (see details below). I am concerned about the many disadvantages that this recommendation hides and I fear for consequences on the future of Go libraries. In this blog post I propose another strategy, which works better common development workflows and is backward compatible with non version aware Go libraries.

![]() I would love to know what you think. Please use the comments platform on the bottom of the post for discussion.

I would love to know what you think. Please use the comments platform on the bottom of the post for discussion.

Copy Strategy

In 1, it is instructed to use a copy strategy by “develop v2+ modules in a directory named after the major version suffix.” This means that introducing a new version, v2.0.0, in a project, should be done by creating a directory v2 in the project root and copying all files from the root directory to the v2 directory. Then, both the root directory and the v2 directory should be initiated as Go modules. If the root is module github.com/user/project, then the v2 directory is module github.com/user/project/v2. Lastly, all imports in the v2 directory should be changed from github.com/user/project(.*) to import the new module github.com/user/project/v2($1).

In 1, the branching strategy is also briefly mentioned: “strategies may keep major versions on separate branches”. Then, it is immediately dismissed: “However, if v2+ source code is on the repository’s default branch (usually master), tools that are not version-aware — including the go command in GOPATH mode — may not distinguish between major versions”. Old libraries that do not support modules, and older versions of Go compiler that do not support versioning are suggested to not work with such strategy. I will show that there is a way to make the branching strategy work in such cases.

Branching Strategy

In this strategy, each version is a git branch. Each code commit is committed to a single version. and versions are marked using git tag (or Github releases) on the relevant branch. Practically, if a developer wants to introduce a new v2.0.0 version, and the current git master points on the last commit of the previous v1 version.

$ git checkout master

$ # Create and push the v1 branch (if was not existed).

$ git checkout -b v1

$ git push origin -u v1

If the repository is yet to have tags (or Github releases), we should tag the v1 branch with a v1.x.x version:

$ git tag v1.0.0

$ git push origin v1.0.0

Now, the module name needs to be renamed and imports are needed to be updated. We can use the same commands mentioned in 1:

$ # Go back to the master branch for the v2 changes.

$ git checkout master

$ # Update project name and imports.

$ go mod edit -module github.com/user/project/v2

$ find . -type f \

-name '*.go' \

-exec sed -i -e 's,github.com/user/project,github.com/user/project/v2,g' {} \;

$ # Commit and push changes.

$ git commit -am "Introduce v2"

$ git push origin master

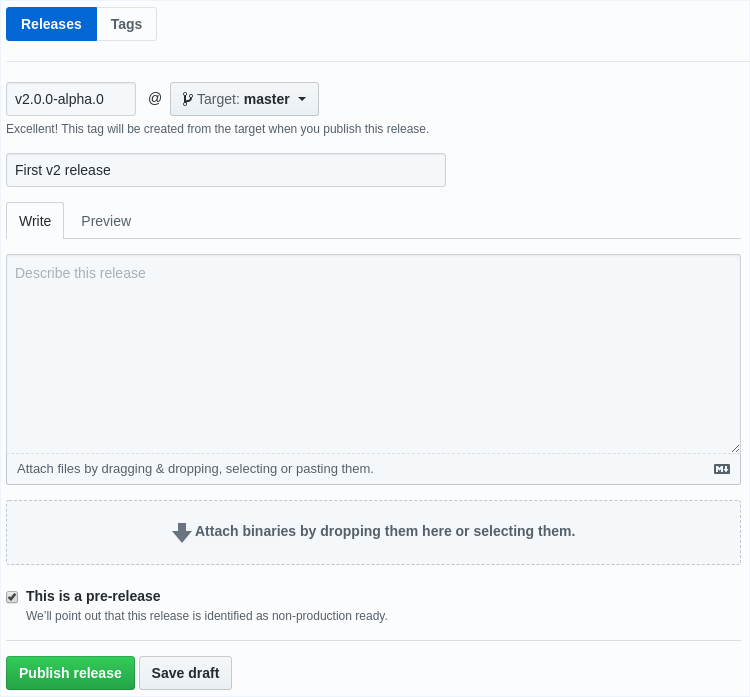

The next step is also similar to the one in 1. Tag a new release from the master branch and push it. I personally prefer to use the Github releases tab, which enables a pre-release (see tip in the appendix section).

$ git tag v2.0.0-alpha.0

$ git push origin v2.0.0-alpha.0

From now on, changes are pushed to the master branch, from which v2.x.y releases are created and fixes are cherry-picked to the v1 branch, from which v1.x.y releases are created.

Comparison

Putting the cards on the table, the branching strategy is the de-facto accepted way to manage versions. A lot of contemporary development processes use branches for versioning, it is used in most open source large scale projects to manage versions, and in fact, also by Go project itself. For the matter of fact, I am not familiar with any big project that uses directories to manage versions. Let’s compare the two approaches in several aspects.

Code duplication: In the copy strategy, the code is copied into a sub directory so there is twice as much code. In this strategy there is no relation between the same files in the different versions: file foo.go has no relation to the file v2/foo.go. When using the branch strategy the same file in different versions are related using the version control system. Tools like git diff can reflect changes between versions.

Backporting: In the copy strategy, when bugs are found and they should be fixed also in old versions, both the project root directory and all versioned directories should be changed. It is not clear if the fix should be applied in one place? both places? in one commit? multiple commits? and the work of applying the change on each of the directory directory is cumbersome. In the branch strategy, the newest should be fixed. The developers can then discuss whether to backport the fix, and the fix can usually be applied on the old versions easily using git cherry-pick and conflicts resolution.

History: In the copy strategy the git history contains changes for all versions. It is confusing and makes it hard to read. In the branch strategy the history of each branch contains only the relevant commits of that version. The branches can be compared using the git show-branch tool.

Project root: In the copy strategy the project root is the oldest version, and also contains files for all future versions. In the branch strategy the project root contains only files relevant for the specific version.

Development workflows: In the copy strategy, if a commit is merged into the master branch, it is not known which of the versions were affected, or if both of them were affected. Marking new releases can actually be done on commits that did not affect the release at all. I also believe that the copy strategy also introduces difficulties in other aspects such as testing, integration with automated tools and understanding the health of the code.

Backward Compatibility Solution

Once convinced to use the branching strategy, let’s discuss how can it work with Go programs and libraries that do not support Go versioning.

First, it is not always a concern. When the project is a program, a tool, or anything else without dependencies, there is no need to make any further changes - it is OK not to support old Go libraries, since there are none. Also, if all the dependencies are known and there is only a handful of them, it might be better to update them to use Go modules. It is easy and will help development velocity in the future.

If it is decided that there is a need to support such Go libraries, there is a simple solution. It is the solution I chose for the complete library.

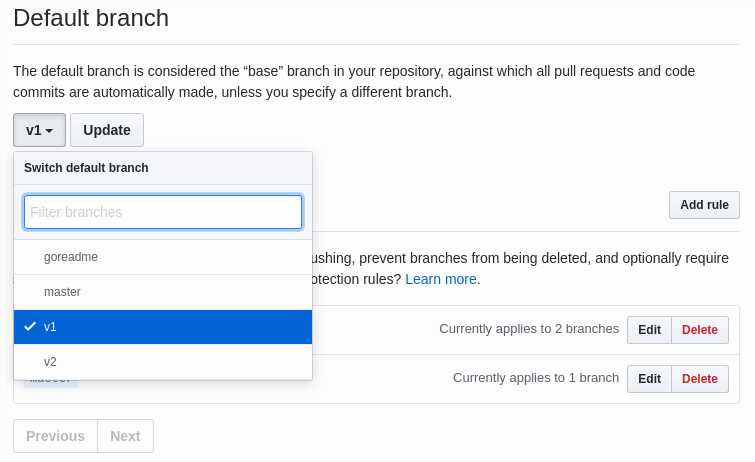

Old Go libraries or old Go compiler, when getting dependencies, take the latest default branch. It we want to support them, a simple solution is to configure your Github default branch to branch v1 (Settings -> Branches -> Default branch).

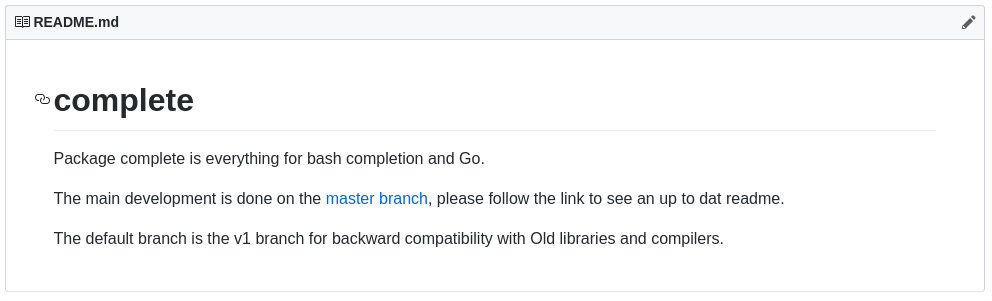

Changing the default branch comes with a minor price of a few esthetic flaws. The default branch for pull requests will be the v1 branch, which can be changed manually every time to master. Some tools that are integrated with the project may not handle it, but most of them know how to handle different branches and not only the default branch. Users browsing your project will, by default, see the oldest version. That is the reason why I propose to update the readme file to reflect and link to the latest development branch.

In my opinion it is a small price to pay, and worth all the benefits of using branches for versioning. If anyone has a better solution, I will be happy to hear about it - please comment below.

Conclusions

In this blog post, I proposed to use the branch strategy to handle Go versioning and explain why it should be the recommended approach. In addition, I also showed how it can work with Go libraries that do not support Go versioning.

When it comes to scaling software, one of Go’s purposes, choosing the branch strategy over the copy strategy is the right decision. In this strategy you can enjoy all git tools for version management, the good familiar developer workflows, a clean project directory and backward compatible library. Additionally, in time, when more and more libraries will convert to Go modules, we could change back the default branch to point on the master branch, and enjoy a duplication-free codebase.

Appendix

Tip: using Github pre-release

When creating a new release, use the pre-release Github check-box. Set the release name as v2.0.0-alpha.0 from the master branch and click the Publish release button.

By using the pre-release checkbox, the release is editable: you can update the release by increment the alpha number and tag a new commit: Click “Edit”, create a new tag v2.0.0-alpha.1, choose the master branch and click Update release button.